Common menu bar links

Human Effects on the Harbour

The seabed of Halifax Harbour contains a wide variety of anthropogenic features (human related) and materials. The greatest density and variety occurs in the inner harbour and Bedford Basin. They include anchor marks, scoured depressions, dredge spoils, borrow pits, shipwrecks, ship-related features, oil-rig marks, dredged and blasted areas, bridge remains, anti submarine net marks, cables, pipelines, trawl marks, sewage banks, and unidentified debris. Smaller debris includes bottles, cans, tires, barrels, metal objects, paper, timbers, and plastics. The following is a description of some of the human caused features and attributes of the harbour seabed.

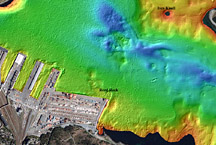

A multibeam bathymetric image of an area of Halifax Harbour between Reed Rock and Ives Knoll. The breakwater to Reed Rock was built in 1913 and it narrowed this part of the Harbour by approximately 25 %.

With the founding of Halifax in 1749 by the British, the harbour seabed and coastline began a new phase of alteration, largely driven by human activities of land clearing, waste disposal, and shipping. The earliest activities were the anchoring of ships in the harbour that produced distinctive patterns of anchor marks on the seabed and eroded sediments. This activity continues today in a more intense way, as much larger anchors and bigger ships are involved. It also includes disturbance and resuspension of sediments by propellers. The early vessels regularly dumped unburned coal, clinkers, and other mixed debris on the seabed and discharged raw sewage. Some of these vessels also sank as a result of storms, collisions, and fire, and over 45 vessels or parts of vessels have been identified on the harbour floor. Other smaller boats may be buried beneath the mud (LaHave Clay).

Early settlers built docking facilities and began the process of infilling areas of the waterfront for a variety of shipping, construction, and industry-related activities. This has continued to the present day with the construction of container piers, housing developments, and waterfront commercial and tourism facilities. A major breakwater was constructed shortly after 1913 in southern Halifax that constricted the main channel into the inner harbour by one-quarter the width. It was built on a shallow bedrock ledge previously called "Reed Rock" and provided a sheltered area for the boat basin of the Royal Nova Scotia Yacht Squadron. Scoured depressions in the LaHave Clay offshore from the breakwater may have formed or been enhanced as a result of this process of harbour narrowing causing an increase in current strength.

Major recent engineering projects, such as the construction of the two bridges spanning The Narrows, and the container terminals, have infilled large areas of the harbour and changed conditions that effect the present and future deposition of sediments. The Halifax Explosion of 1917, the world’s largest manmade explosion prior to the atomic bomb, took place in The Narrows. It only altered the seabed in a minor way. The majority of the damage was on land and the seabed was altered more by the post explosion dredging efforts to remove debris and the remains of Pier 6 and Pier 7 for safe navigation and construction of future shipbuilding and repair facilities.

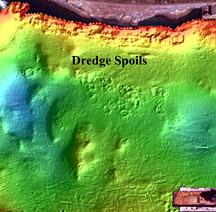

A multibeam bathymetric image of an area of The Narrows of Halifax Harbour showing a cluster of circular dredge spoils on the seabed. These dredge spoils may represent material from the cleanup of the Halifax Explosion.

Dredge spoils are deposits of material discharged to the seabed by barges. They consist of a wide variety of materials such as sediments, contaminated sediments, construction debris, docking materials, gravel, boulders, garbage, and unidentifiable debris. The dredge spoils range up to 40 m in diameter and are generally circular. Dredge spoils at the entrance to Northwest Arm have also been dumped on LaHave Clay (mud), compressing and displacing it into depressions that resemble pockmarks (gas-escape craters). In some areas these dredge spoils have resulted in the venting of the gas-charged sediments directly beneath the spoils.

The largest occurrence of dredge spoils is in the Bedford Basin where approximately 200 have been identified covering approximately 5% of the deep basin floor. They also occur as raised areas at several locations in The Narrows and are scattered about the seabed of other areas of the inner harbour. Very few were found in the outer harbour. The practice of dumping dredge spoils in the harbour has been largely discontinued.

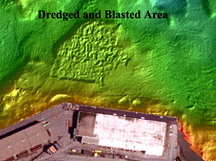

A multibeam bathymetric image from an area of The Narrows that was blasted and dredged to increase water depths. The feature was a bedrock high.

Many areas of the harbour bottom have been dredged to provide deeper water for the passage of large vessels. A drumlin (Little Georges Bank) adjacent to the naval dockyard in Halifax has been dredged with a clam-shell bucket. Remotely operated vehicle observations, sidescan sonograms, and multibeam bathymetry over the drumlin show a rough relief of 2 m. The drumlin is made of till that is a mixture of gravel, sand, silt, and clay. Boulders are widespread and organic growth (such as plants and algae) and benthic organisms are absent on this dredged drumlin, locally called "Little Georges Bank".

Dredging for fill has taken place in Bedford Bay near the mouth of the Sackville River. This material was pumped through pipelines in a water-sediment slurry to a large land reclamation area in western Bedford Bay where a modern housing development has taken place. Extensive dredging has been located adjacent to the former Texaco Canada refinery dock in the Eastern Passage.

An area of seabed adjacent to Pier 9 in The Narrows has been blasted to increase depth. Here the sidescan sonograms and seismic-reflection data indicate that the shallow area has Halifax Formation slate bedrock at the surface of the seabed.

The Narrows is the shallowest area of hard seabed in the harbour and may require future dredging to accommodate the passage of the next generation of large container ships in to the Bedford Basin. There are many large boulders on the seabed and the cribwork remains of the first bridges crossing The Narrows, this may need to be removed for safe vessel passage. Dredging is common in large harbours undergoing maintenance and expansion and this activity will likely continue in Halifax Harbour.

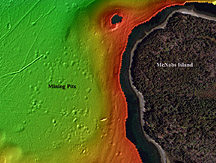

A multibeam bathymetric image from the seabed of Halifax Harbour to the north of McNabs Island showing aggregate mining pits at the seabed left from the removal of sand and gravel.

Mining for placer gold was one of the earliest projects in Halifax Harbour. A small quantity of gold was recovered. Aggregates (sand and gravel) are some of the most important materials to be mined from the sea. Borrow pits are circular to linear seabed depressions formed by the removal of aggregate through dredging techniques. The largest area of borrow pits occurs in a dense cluster directly north of McNabs Island and east of Ives Knoll. The pits average 15 m in diameter and range up to 3 m in depth.

A series of large, linear, and oblong pits occur in the nearshore off eastern McNabs Island. They are up to 300 m long, 50 m wide, and 5 m deep. Large quantities of material were removed during the 1950s and 1960s from these pits to supply aggregate for construction. They do not appear to be infilled with fine-grained sediment, confirming there has been low sedimentation rates on the flanks of McNabs Island in Eastern Passage since their formation.

A multibeam bathymetric image of the central part of Bedford Basin showing many anchor marks at the seabed.

Marks on the seabed formed by ship anchoring are widespread, especially in Bedford Basin and the inner harbour. They form a small-scale roughness on the sediments up to two metres deep.

Sidescan-sonar records provide the most detailed information on anchor-mark character and distribution. Only some of the larger anchor marks show on the multibeam-bathymetric imagery. One of the most important aspects of anchor marks is that anchoring disturbs and turns over the sediments. This nicknamed "anchorturbation".

Anchor marks are classified into three major types: anchor pits, anchor-drag marks, and anchor-chain marks. Anchor-chain marks are further subdivided into anchor-chain-link marks.

Maps showing the distribution and density of anchor marks on the seabed of Bedford Basin and inner Halifax Harbour.

Anchor marks occur in a variety of depths, sizes, and shapes. The largest ones are up to 2 m deep and 5 m wide. Anchor marks on gravelly, hard seabed tend to be shallow, most often less than 1 m deep, but are clearly defined because of the presence of boulders in their berms, piles of sediment. Some have been traced for over 3 km along the seabed of the harbour. Many of the large harbour docks display radiating patterns of anchor marks indicating that anchors are used to help ships dock.

Most of the anchor marks occur in LaHave Clay (mud) sediments as both the anchoring and sediment deposition generally takes place in the deepest areas of the harbour. In the inner harbour, the densest distribution of anchor marks occurs in the broad region to the north, east, and southeast of Georges Island. This is the area of the harbour designated for anchoring. In Bedford Basin over 80% of the muddy seabed is criss-crossed with anchor marks. The densest distribution occurs in the central deep-water area with water depths generally greater than 50 m.

Some of the anchor marks are very old. Those in Bedford Basin are interpreted to have formed during World War I and II when large convoys of military and merchant ships assembled and anchored over broad areas of the basin, prior to sailing across the north Atlantic Ocean to Europe.

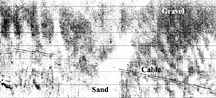

A sidescan sonar image of a cable on the seabed of Halifax Harbour. Where the seabed is sand the cable is buried and where it is gravel it lies on the seabed.

Cables are common on the seabed of Halifax Harbour. They show up well on sidescan-sonar records as linear, narrow features. In the early days of undersea telecommunications, many cables extended from Halifax Harbour to points in Europe. Early charts of the harbour indicate up to 30 cables on the bottom. Today most of these cables have been abandoned.

Another set of seabed cables was used by the military. During the wars, coils of wire were used for magnetic detection of enemy vessels and submarines. Explosive devices were positioned on the seabed and connected with additional cables for detonation. Some of the cables also remain on the outer harbour seabed. The cables in the outer harbour can provide a benchmark for understanding sediment transport. Sidescan sonograms show cables buried in places beneath sand bedforms, indicate sediment mobility.

Modern telecommunication and electrical transmission cables cross the harbour and connect Georges, Devils, and McNabs islands with the mainland. Other cables on the seabed of the harbour are used in military applications for acoustic, magnetic, and degaussing ranges.

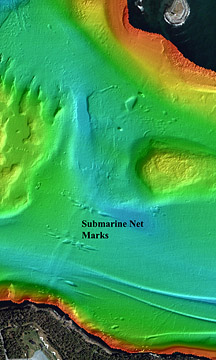

A multibeam bathymetric image of the seabed of Halifax Harbour in an area where anti submarine nets were positioned during World War II. Slight depressions occur on the seabed beneath where the nets crossed the Harbour. Larger depressions are the result of current scour around concrete weights used to hold the nets in place.

The World Wars I and II and associated military activities have had a large influence on the seabed of the harbour. Convoys of ships assembled in the harbour and Bedford Basin before leaving for Europe. These ships anchored over large areas, eroding and mixing sediments as well as discharging materials to the seabed. Their fingerprint from these activities still remain today. Submarine detection and destruction devices were placed in the outer harbour and were connected with electrical transmission cables, some of which remain on the harbour seabed. Antisubmarine nets were strung across areas of the harbour to control the passage of submarines. Remains of these structures are still present on the harbour bottom. Since we know the date when these were created, they can be used to assist in understanding processes of erosion and deposition. Recent military activities include the emplacement of acoustic and magnetic sensors on the seabed.

Two parallel linear depressions occur in the outer harbour extending between Sandwich Point and Maugher Beach. They are interpreted to have formed beneath antisubmarine nets that spanned the harbour in this location during World War II. Scouring of the seabed around the base of the nets is interpreted as the mechanism responsible for formation of these depressions.

A series of deeper scoured depressions at right angles to the antisubmarine net marks also occurs in the same area. Sidescan records show large square concrete blocks on the seabed with scoured depressions to a depth of several metres between the blocks. The scoured depression around the blocks forms an arrow-shaped feature that points south. The erosion is concentrated only around the blocks and the shape of the depressions indicates that the currents that form them are from the south.

An artists (Derek Sarty) representation of the Trongate sitting on the bottom of Halifax Harbour and squeezing up the soft mud on both sides of the hull.

A linear pattern of isolated depressions occurs in the central and northwest area of Roach Cove, Bedford Basin. A further grouping of overlapping depressions occurs in the eastern area of Roach Cove. These features are formed in LaHave Clay and are interpreted as blast pits formed by the military test detonation of ordnance.

One of the most unusual and difficult to interpret features on the seabed of Halifax Harbour is a feature termed the "Trongate depression". It is a linear depression 125 m in length, deeper at one end, with flanking piles' or berms, of mud. The largest berm extends 2 m above the surrounding seabed. The feature was formed by the sinking of the Norwegian vessel, the S.S. Trongate, a 7000 tonne merchant ship that was purposely sunk in 1942 because of an onboard fire and an explosive cargo. It was later salvaged, but the impression of the hull remains in the mud as the ship squeezed the mud upward at anchorage number 4, north of Georges Island.

A photograph of unexploded ordnance (.303 bullets and cordite – white straw like material) at the location of the Trongate sinking in Halifax Harbour.

Remotely operated vehicle observations show the presence of rolls of newsprint, wooden planks, boots, and much debris at the location. In 1993 a large cache of unexploded ordnance, which included primed 10 cm shells, cases of .303 rifle ammunition, and scattered cordite (explosive), were found at the Trongate depression. Because of the presence of this pile of unexploded ordnance, anchoring is no longer permitted at this location.

A group of approximately twenty-five 1969 Volvo automobiles were found on the seabed of Bedford Basin in 60 m of water. They were dumped onto the seabed after they incurred severe water damage in transit across the Atlantic Ocean on a container ship. They provide excellent seabed targets for sidescan-sonar and multibeam-bathymetry equipment trials. Other automobiles have been found on the seabed of the harbour adjacent to the downtown docks and are suspected to have been purposely discarded to the seabed.